What’s going on with the invasive lionfish?

Ask anyone around the southeastern United States and they’ll tell you the same thing: we’ve got to get rid of the invasive lionfish. Originally from the Indo-Pacific, these fish have been catastrophic to the environments in the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean, and Atlantic. In fact, NOAA estimates a single lionfish on a reef can reduce Florida’s native fish recruitment by 79 percent.

Shown here is the invasive red lionfish that’s haunting Florida. Despite being troublemakers, they’re beautiful animals. Photo by Ray Harrington on Unsplash

However, there’s more than one lionfish species. As a matter of fact, there’s sixteen— two of which hail from Hawai’i. These are the Hawaiian red lionfish, also known as the turkeyfish (Pterois sphex), and the Hawaiian green lionfish (Dendrochirus barberi).

That fact alone can make any gator-wrestling Florida Man quake. Which begs the question…

Do we need to do something about the Hawaiian lionfish?

Shown here is a Hawaiian red lionfish, or turkeyfish. They look similar to their invasive cousins. Uploaded by desertnaturalist on iNaturalist

Surprisingly, no.

Hawaiian lionfish are endemic, meaning they originated in Hawai’i. They haven’t taken up residence in other locations, unlike their cousins who’ve invaded Florida. Getting rid of the Hawaiian lionfish would mean eliminating a native population (and the human Hawaiians already got that check in the box, thank you very much).

For many years, Hawaiian lionfish were captured and sold to aquariums. That resulted in a decline in their wild populations. So in one part of the world lionfish are out of control, and in another they need to be protected. It’s bonkers that that happens, but here we are.

What are the differences between invasive and Hawaiian lionfish?

A Hawaiian green lionfish. Uploaded by coralreefdreams on iNaturalist

The lionfish in Florida are larger, measuring in at around 18 inches as adults. The Hawaiian green lionfish— considered a dwarf lionfish— maxes out around 6.5 inches (Hoover, 2008). The Hawaiian red is around 8 inches.

Also, you can’t find Florida’s invasive lionfish species in Hawai’i (and vice versa).

The Hawaiian green lionfish has a mottled brown and green coloration. This helps them blend into the rocky reefs they like to squeeze between during the day. Unlike the red lionfish, the Hawaiian green has fan-like pectoral fins. They lack the trailing fronds of their cousins, but have bright red eyes.

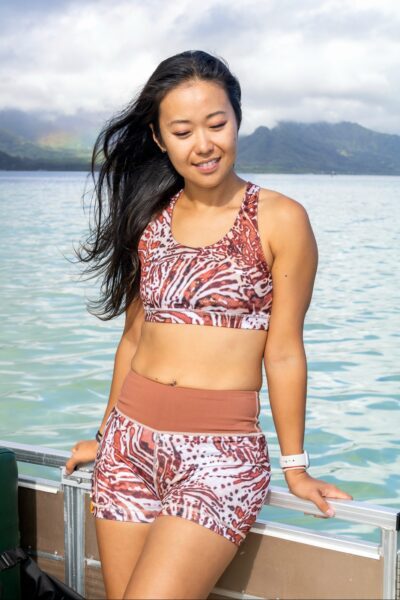

Lionfish have dramatic, eye-catching patterns— why not wear it? Shop Nudi Wear’s lionfish series. Photo by Anabel Cepero.

Both the invasive red and Hawaiian red lionfish species sport dramatic red and white stripes. Those are paired with delicate, frilled pectoral fins. The spines on those fins are long, finger-like, and filled with venom. Despite the trouble the invasive lionfish causes, it’s no wonder why they’ve become the poster-child for invasive species: they’re hauntingly elegant, yet vibrant in color.

Very fashionable.

Fashionable to the point that it is fashion. Shop our Lionfish Activewear Series here.

Can Hawaiian lionfish sting you?

Yes! Lionfish are part of the larger scorpionfish family. They’re not called scorpionfish because their sun sign is Scorpio (side note: lionfish can produce offspring year-round— statistically one has gotta be a Scorpio). Like scorpions on land, these fish use venom as a natural defense against predators.

If you’re stung, the pain can last hours to days depending on the species and sting intensity. Anecdotes from divers say that the Hawaiian red is much more painful than the green lionfish (Hoover, 2008).

A lionfish’s venom is similar to a cobra’s, but isn’t typically fatal. Most people don’t seek medical treatment (source). The best thing you can do if stung is to submerge the affected area in hot water.

The Hawaiian word for the red lionfish is nohu pinao, which means “dragonfly,” whereas its Latin species name sphex means “wasp.” Makes you wonder if the person who came up with the Latin name was stung.

Are Hawaiian lionfish aggressive?

Nope. They don’t seek out people, and are actually rare to spot, like that one cousin at a family reunion. They’ll only sting you if they feel threatened (and only talk to you if Minecraft is downloaded on your phone).

As nocturnal creatures, Hawaiian lionfish come out at night to hunt small fish and crustaceans. They spend the day hanging under rocky overhangs, like that one coworker who quit to become a rock climber. Just like that coworker, they’ve been known to frequent a favorite spot for years (Hoover, 2008). So if an unknowing diver sticks a hand in one of these spots, they may get a nasty sting.

Can I eat one?

There’s no regulation on catching lionfish for food in Hawai’i. However, they’re small, hard to find, and not great for eating. Plus, you run the risk of getting stung, or giving yourself ciguatera poisoning if you’re not careful about your cooking.

In the southeastern United States it’s a different story. To regulate the invasive lionfish, people are allowed to catch and eat them for population control. Out in Hawai’i, there’s no need to control their numbers.

Since they’re considered “ornamental,” the Hawaiian lionfish was hit by the aquarium trade. Their population is still recovering. Best to leave this fish alone.

Have you ever spotted a lionfish in the wild? Or eaten one down in the Caribbean? We’d love to hear about it! Drop a comment below.

Non-linked Source:

Hoover, J. P. (2008). The Ultimate Guide to Hawaiian reef fishes sea turtles, dolphins, whales, and seals. Mutual Publishing.

Leave A Comment